As the world’s fastest-growing economy last year, Ethiopia is expected to continue its spectacular economic performance under its new prime minister, Abiy Ahmed. However, he must address the country’s inherent problems with energy supply and infrastructure to sustain this success

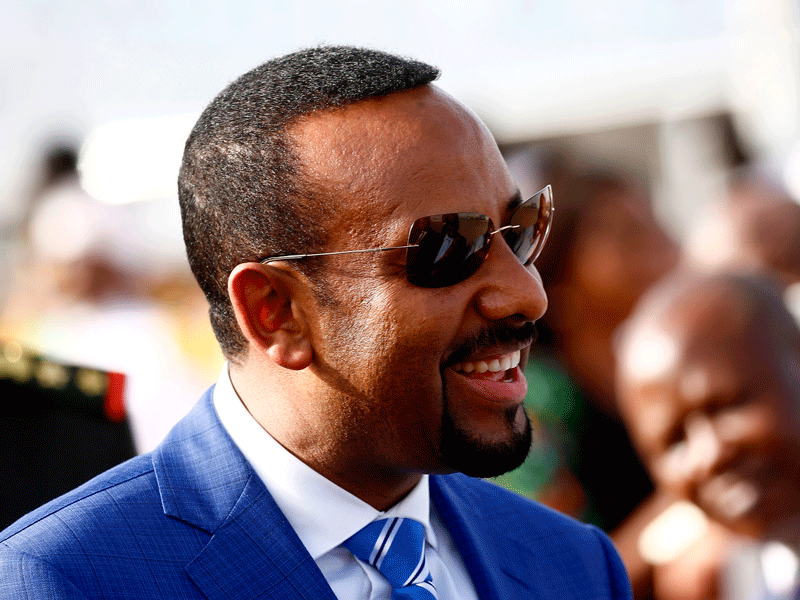

Perhaps what had been missing from the tale until now was a charismatic protagonist. Enter Abiy Ahmed, as of April 2, Ethiopia’s 15th prime minister. Abiy has taken the country by storm, and in just a few months has achieved what most leaders could only hope for during an entire tenure: establishing peace with neighbouring Eritrea; rousing a disenchanted population; pushing forward with key infrastructure development; opening up the economy to further financial investment; and winning support from the Ethiopian diaspora.

A unifying force

Heading up the Oromo People’s Democratic Organisation – one of four parties comprising the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front coalition – Abiy is Ethiopia’s first prime minister from Oromia, the country’s biggest ethnically based state.

At 42, he’s the youngest leader on the African continent. His youth is reflected in his style of leadership, his stirring rhetoric and the speed with which he is taking action – in short, Abiy is a breath of fresh air. Since coming to power, he has made moves to modernise the economy and loosen the monopoly of key sectors. This news is a boon to the aviation industry in particular, given Ethiopian Airlines’ status as Africa’s largest and fastest-growing airline. Competition for a 30 to 40 per cent stake in state-run Ethio Telecom is also heating up.

A decade of growth

Naturally, a number of the successes sparking international admiration were already underway before Abiy came onto the scene. Indeed, last June, the World Bank labelled Ethiopia the world’s fastest-growing economy. According to a new report by the organisation, its GDP growth for the 2017 fiscal year reached an excellent 10.9 per cent, while growth for the period from July 2017 to June 2018 is forecast at 9.6 per cent.

It’s very important to stress that it is not only a sustained period of very rapid growth, but it was also achieved in a country that is not resource-rich. It’s not a matter of being driven by oil, diamonds and so on. So it is quite an unusual record and very important in the context of sub-Saharan Africa. Despite this lack of resources and the fact that it is landlocked, Ethiopia has managed to increase its GDP tenfold since 2000. Extreme poverty, meanwhile, dropped by over 20 per cent between 2000 and 2011.

Ethiopia’s shift from recurrent to capital expenditure has formed the foundation of the country’s socio-economic transformation, its focus on infrastructure development, in particular, being instrumental.

“Many orthodox economists tend to criticise high government spending in lower-income countries, but what you notice is that to some extent grudgingly, many people have come to accept that it has been really important in Ethiopia. So you’ll see World Bank economists, for example, acknowledging that a set of heterodox policies, combining around a programme of large-scale public spending, has been at the basis of this period of growth.”

Filling the transport void

Despite its rapid GDP growth, Ethiopia’s woeful transportation infrastructure has acted as a stranglehold on the economy for decades. In 1990, the country – which is around twice the size of Texas – had just 19,000km of roads. Transforming this situation has been crucial. Thanks to the government’s refocused spending ($11bn has been spent on roads over the past two decades) together with a growing inflow of foreign investment (FDI has increased fivefold from $814.6m to $4.17bn between FY 2007/08 and FY 2016/17), by 2015 Ethiopia’s roads stretched 100,000km around the country. Showing no signs of abating, today foreign investment continues to bolster the network, while 20 per cent of the government’s infrastructure spending is dedicated to road building, equating to $1.7bn annually.

Railway construction is another symbol of the government’s determined strategy. In September 2015, a new 32km light rail system opened in the country’s capital, the first of its kind in sub-Saharan Africa. The Chinese-funded project has enabled some 60,000 citizens from the city’s suburbs to travel into the centre for work – and affordably, too. Further plans are in the pipeline to connect the electrified network with the national train system by 2025, earmarking the government’s plans to become a transportation hub for neighbouring countries.

The 750km-long electric railway connecting Addis Ababa to the Red Sea via the Port of Djibouti best encapsulates this aim. Inaugurated in October 2016 and beginning commercial operations in January 2018, the line reduces transit time from two-to-three days to around 10 hours. With faster and cheaper access to the sea through Djibouti, the railway is a boon to the country’s burgeoning manufacturing sector.

Behind such assertive plans is a coherent approach to leadership, which is pivotal in the economy’s transformation.

Ethiopia’s recent economic success can also be accredited to pragmatic – rather than ideological – leadership. They are very willing to learn from a range of other countries’ experiences and to talk to all manner of people – from western investors, the IMF and the World Bank to the Chinese Communist Party. They study the record of industrial paths in Vietnam, Mauritius and elsewhere before making their own strategic choices. That pragmatism goes with a willingness sometimes to learn from mistakes and to adjust direction and move forward.

An enticing investment

Such infrastructure development has obvious effects on the economy, but there is another reason pushing the momentum forward so rapidly: Ethiopia’s vision to become a manufacturing hub. In recent years, the nation has boasted formidable success in using its very competitive rates to persuade foreign manufacturers to set up shop in the country.

One of the first such manufacturers was Huajian Group, a Chinese shoe manufacturer that employs around 4,000 people in an industrial park outside the Ethiopian capital. Big-name clothing brands have since followed suit, including the US’ Gap, Germany’s Tchibo and Sweden’s H&M. In 2017, the industry received another windfall when not one but three fashion giants set up factories in the country: PVH, of Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger fame; Velocity Apparelz Companies, which boasts the likes of Zara and Levi’s; and Jiangsu Sunshine Group, the manufacturer for Hugo Boss and Giorgio Armani. According to Ethiopia’s investment commission at the time, a further 150 companies from China and India would soon begin sourcing production from Ethiopia.

The government itself is very focused on industrialising and is serious about developing Ethiopia as a manufacturing destination.

Its goal, former prime minister Hailemariam Desalegn told reporters when Hawassa became fully operational in July 2017, is to create “millions of new jobs in labour-intensive and export-oriented light manufacturing”. He added: “The Hawassa industrial park is the most evident and concrete example yet towards achieving our national vision, and marks a milestone in our quest for industrialisation.”

Being one of the country’s greatest assets, Ethiopia’s enormous population is at the core of this mission. Importantly, the people are ready and willing. Many of them think that the concept of working in factories is good for the country – there is that sense of patriotism and wanting the country to succeed.

Quenching the power thirst

Though Ethiopia is the rising star of light manufacturing, challenges remain, ranging from those of bureaucracy to issues with cotton quality. However, the most pressing is the issue of energy stability.

For too long, energy apartheid has stifled countries in sub-Saharan Africa – Ethiopia is no exception.

While many investors are hopeful that the country’s new industrial zones will result in large-scale garment assembly and manufacturing, the unreliable supply of electricity is a concern.

The government is aware of the importance of overcoming this particular challenge. Fortunately, it is taking advantage of the country’s hydroelectric potential and has built several dams in recent years, including the GERD, whose potential is tremendous. With an expected generation capacity of 6,450MW, the GERD project is set to become the biggest dam in Africa.

These kinds of projects have the potential to start to overcome the power shortage.

Significantly, the GERD will also act as a driving force for exporting electricity to neighbouring nations, which in turn will prove crucial to generating foreign exchange. Indeed, the dam has become a powerful symbol for the country. Costing a whopping $4.7bn, the GERD has been funded and constructed almost solely by Ethiopians, marking a monumental step in the state’s ability to stand on its own two feet and demonstrating its status as a regional power.

The best is yet to come

Ethiopia is now on the cusp of a complete transformation. Its remarkable economic growth makes it a beacon of inspiration for the entire region; indeed, it holds a number of lessons from which other developing nations can draw. First, it highlights the importance of government spending – even in low-income countries – particularly in areas that are stifling the economy. In Ethiopia, the government has maintained a determined focus on improving transportation and energy infrastructure, and it has done so through a combination of local financing, the facilitation of foreign investment, securing loans from international entities and the help of the diaspora.

Now with Abiy at the helm, the economy has received yet another boost, thanks in large part to his quick work and charisma. Today, the country is more stable than it has been for years – foreign investors are further motivated, while the population is amply inspired. The time is ripe for the country to firmly push itself into the next phase of its development: becoming a hub for sub-Saharan Africa in terms of manufacturing, transportation, energy and economic leadership. With more reliable energy soon to follow, the country’s grand ambitions are actually within reach. Ethiopia’s economic story is truly extraordinary – and the best part is, it’s not over yet.

Source: World Finance